Ghostwritten is David Mitchell's first novel, and on finishing it, I've now read all his works, which pleases me greatly. Of course, the fact that this is a tremendous debut adds to the pleasure, albeit, I really do wish there was another Mitchell on my shelf, just waiting to be read.

The sub-title of the book reads, "a novel in nine parts," and so it is. It could easily a collection of nine short stories, each told in first person by a different narrator, who seemingly have nothing to do with the previous narrator(s). However, six degrees of separation (or fewer) bind the characters together, through time and different geographical locations. The link between the characters isn't blatantly evident though, as one might come to expect from Mitchell, and at times, it's confusing as to how the characters come together, and to figure out if there is any kind of causal sequence. That said, one can't help but anticipate the revelation of the link, and then deliberate over it for a bit, which in turn means that one can't help but read the book, scrutinising almost every word to see where the link lies.

Ghostwritten is David Mitchell's first novel, and on finishing it, I've now read all his works, which pleases me greatly. Of course, the fact that this is a tremendous debut adds to the pleasure, albeit, I really do wish there was another Mitchell on my shelf, just waiting to be read.

The sub-title of the book reads, "a novel in nine parts," and so it is. It could easily a collection of nine short stories, each told in first person by a different narrator, who seemingly have nothing to do with the previous narrator(s). However, six degrees of separation (or fewer) bind the characters together, through time and different geographical locations. The link between the characters isn't blatantly evident though, as one might come to expect from Mitchell, and at times, it's confusing as to how the characters come together, and to figure out if there is any kind of causal sequence. That said, one can't help but anticipate the revelation of the link, and then deliberate over it for a bit, which in turn means that one can't help but read the book, scrutinising almost every word to see where the link lies.

{note: there are some spoilers below, but I have tried to keep them to the minimum}

The first story, Okinawa, is inspired by the Sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway - an act of domestic terrorism. Quasar, a terrorist, is on the run after wreaking havoc on a train, as he imagines a world without the "unclean" - forgive the comparison, but similar to the way some pure-bloods (and Voldemort and his Death Eaters) fell about mud-bloods in Harry Potter. Quasar believes he can communicate with the leader of his cult telepathically, and while he hides out in Okianawa, waiting for things to quieten down, he gets the news that His Serendipity has been captured. While the locals rejoice, Quasar tries to get in touch with the powers that be, to figure out the next course of action. The password to get in touch with the powers that be is simply, the dog needs to be fed.

Cue the second story, and the shift in location to Tokyo, where a teenager works in a record store, specialising in jazz. One day, a group of girls enter the store, and he's instantly attracted to one of them, but they leave the store, and he is resigned to never meeting her again. A few days later, while he's closing up the store, he hears the telephone ring, and being conscientious, goes in to answer the phone. The voice at the other end simply says, it's Quasar. The dog needs to be fed. As fate has it, this slight delay leads to him meeting the girl again, and they immediately hit it off. End of the second story. Yes, the links are that random.

“The last of the cherry blossom. On the tree, it turns ever more perfect. And when it’s perfect, it falls. And then of course once it hits the ground it gets all mushed up. So it’s only absolutely perfect when it’s falling through the air, this way and that, for the briefest time … I think that only we Japanese can really understand that, don’t you?”

{end of spoilers}

Through the rest of the stories, the reader meets the Russian mafia, and a ghost that transfers from being to being by touch; a physicist involved with the Pentagon and a night-time DJ in New York; a tea shack owner at the Holy Mountain who laments as to why women are always the ones who have to clean up, and a drummer/writer in London who also works as a ghostwriter to pay the bills.

I couldn’t get to sleep afterwards, worrying about the possible endings of the stories that had been started. Maybe that’s why I’m a ghostwriter. The endings have nothing to do with me.

You know the real drag about being a ghostwriter? You never get to write anything that beautiful. And even if you did, nobody would ever believe it was you.

We're all ghostwriters, my friend. And it's not just our memories. Our actions too. We all think we're in control of our lives, but they're really pre-ghostwritten by forces around us.

The above quotes illustrate another prominent aspect of the book: the role of fate, of chance, of the chain-reaction. The sheer randomness of the stories, and the way the characters inter-connect is pivotal to the novel, and keeps the reader completely engrossed. Of course, the other side is, by the time the reader actually starts relating to the narrator or nodding in agreement with their sentiments, a new narrator is introduced and the old narrator a thing of the past.

And then there's sneaky little political comments just dropped, making the book a lot more relevant in today's day and age. The below snippet, for example, reminds me of the preamble to Iraq.

"Have you noticed," said John, "how countries call theirs 'sovereign nuclear deterrents,' but call the other countries' ones 'weapons of mass destruction'?"

It's an overtly ambitious work, with some fairly profound statements, that had me admiring the debut from the get-go. It was thought-provoking and massive - perhaps not as demanding as Cloud Atlas, but a hell of a ride, nonetheless, and one couldn't help but marvel at how it all unraveled.

Integrity is a bugger, it really is. Lying can get you into difficulties, but to wind up in the crappers try telling nothing but the truth.

Of course, the other impressive thing was, how all nine narrators found a unique voice in the novel, totally disconnected from the previous narrator, similar to Cloud Atlas. Speaking of his most acclaimed book so far, two characters from Cloud Atlas also made an appearance in this book: Tim Cavendish and Luisa Rey - their occupations remain the same across the books, i.e. publisher and writer respectively. Not only that, but a character with a comet-shaped birthmark has a cameo role to play as well. I have to say, love finding old friends in new books!

Personally speaking, my primary complaint with the novel was that I didn't get a sense of closure or fulfilment on finishing the book. I enjoyed it, but I just didn't get the ending. I re-read the last "story" thrice, but to not much avail. I believe this book would benefit from a re-read, as there might have been a multitude of subtle hints that I missed - inadvertently.

Have you read David Mitchell's debut novel? Or, anything by him? What's your favourite? My unequivocal pick would be Number9Dream, but that might have something to do with it being the first Mitchell I read. I almost feel as though I have to re-read all his works in the order of writing, to truly appreciate the erratic wondrous world of fiction he has created.

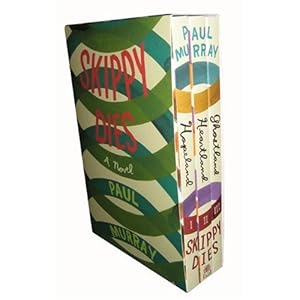

Paul Murray's second book, Skippy Dies, has been long listed for the

Paul Murray's second book, Skippy Dies, has been long listed for the  I

I  Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2008, and winner of the Costa Award 2008, The Secret Scripture explores the lives of both, Dr. Grene (a psychiatrist) and his centerian patient, Roseanne, as both characters reflect on their life from their youngest days, to where are they at this point in time.

Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2008, and winner of the Costa Award 2008, The Secret Scripture explores the lives of both, Dr. Grene (a psychiatrist) and his centerian patient, Roseanne, as both characters reflect on their life from their youngest days, to where are they at this point in time. I'm trying to read all the Booker winners, in the next couple of years. This painstakingly dull book, filled with unengaging characters and a pointless plot adds a serious blemish to my plan at the very outset. I struggled through the first thirty pages, and struggled some more 'til I hit page 89, in a week... And then... then I just gave up, and figured this book is not for me. I mean, what a gigantic waste of my reading time!

I'm trying to read all the Booker winners, in the next couple of years. This painstakingly dull book, filled with unengaging characters and a pointless plot adds a serious blemish to my plan at the very outset. I struggled through the first thirty pages, and struggled some more 'til I hit page 89, in a week... And then... then I just gave up, and figured this book is not for me. I mean, what a gigantic waste of my reading time!