It was in September 2009 when I purchased Atwood's Oryx and Crake, and it's been sitting on my shelf since, feeling slightly neglected. I've heard mixed reviews about the book, so procrastination played its part in the delay, but I finally did pull it out, being in the mood for some post-apocalyptic fiction.

My Atwood point-of-reference is The Handmaid's Tale, a book I can't recommend enough, and considering that, I thought this fell slightly short of my expectations. It might be because The Handmaid's Tale sets an incredibly high standard. I mean, all said and done, Oryx and Crake was shortlisted for both, the Booker Prize and the Orange Prize.

It was in September 2009 when I purchased Atwood's Oryx and Crake, and it's been sitting on my shelf since, feeling slightly neglected. I've heard mixed reviews about the book, so procrastination played its part in the delay, but I finally did pull it out, being in the mood for some post-apocalyptic fiction.

My Atwood point-of-reference is The Handmaid's Tale, a book I can't recommend enough, and considering that, I thought this fell slightly short of my expectations. It might be because The Handmaid's Tale sets an incredibly high standard. I mean, all said and done, Oryx and Crake was shortlisted for both, the Booker Prize and the Orange Prize.

There's Jimmy, who has witnessed (and played a part in)the apocalypse, and is the lone human survivor, along with the children of Crake (called Crakers), and many genetically modified animals, including pigoons (a cross between pigs and raccoons used to harvest organs), rakunks (a cross between rats and skunks, which have no purpose but to serve as pets) and scary wolvogs. He reflects on the past and how he's ended up where he is, as he tries to figure out a way to survive this new reality.

Jimmy's childhood is an exaggeration of life as we know it: Online gaming and communities, pornography, watching live execution channels, playing chess and just hanging out with Crake, his closest friend. Yet, he grows up in a compound where pigoons were created and continue to be genetically modified so as to harvest more organs, and he has a rakunk as a pet. Negligent parents, no siblings, same story.

Yet, where Jimmy is ordinary, Crake is extraordinary. He is competitive, intelligent, and envisages a futuristic society where immortality can be contemplated.

Immortality [...] is a concept. If you take ‘mortality’ as being, not death, but the foreknowledge of it and the fear of it, then ‘immortality’ is the absence of such fear.

And, he conceives a world where the inhabitants are inherently nonchalant about sex and violence. They are stronger, prettier, more resilient, and can handle the stronger UV rays after the ozone layer depletes. Then, he plays god, and so, the children of Crake are born. Crake's focus on science and complete disregard of humanity as is (must end the world to create a better one philosophy) is almost scary. At what point does anyone have the right to play god? And who, if anyone, is there to check him? It might not be possible as things stand, but what if a couple of centuries later, someone did figure out how to bring "better" people into the world? Or, why not just leave life to evolution? Is that being too boring?

"As a species we're doomed by hope, then?"

"You could call it hope. That, or desperation."

"But we're doomed without hope as well," said Jimmy.

"Only as individuals," Crake said cheerfully.

"Well, it sucks."

"Jimmy, grow up."

Crake wasn't the first person who had ever said that to Jimmy.

While the Crakers were still being "developed" and taught, the deadly virus strikes, killing everyone but Jimmy, who has never interacted with them earlier, but has promised Oryx that he would take care of them, if disaster struck. It's almost as though she knew what was coming...

Oryx - the sole female protagonist - stayed calm, composed and unearthly throughout the book. Not prone to any extremisms, and in a state of perpetual indifference, Oryx almost came across as a robot. Strange as she had been sold by her parents to a gentleman, and eventually ended up as a child porn star, after which she encountered a string of unpleasant things. But her lack of emotions just made her seem too far and too distant from reality (whereas, I think, the gross exaggeration of Jimmy's childhood gets the reader closer to him).

And so - when Oryx and Crake, and everyone else die, Jimmy starts looking after the Crakers and answering the multitude of questions they throw his way - most of the answers he just makes up as he goes along. Crake has a god-like status amidst his "children" and Jimmy (or Snowman as he is now known) a demi-god-like status. He tries to use it to his advantage, but he really does try to do the right thing. That's what makes Jimmy's character slightly blasé: things happen around him in spite of him. He is not a catalyst, he is not the chemical - he's just the neutral, watching things unfold.

I think that's where my problem with the book lay the characters! I found I cared little, if at all, about them. Honestly, the only character that seemed to have a real role was Crake, but the narrative was such that it didn't give us much insight into him. Instead, the narrative centred around Jimmy and his battles as he lives with the Crakers by the beach, trying desperately to just - survive. Just thinking aloud - I think it would have been extremely interesting if the book was written from the point of view of Crake, and what was driving him. We get a high-level insight into his philosophies, but... I felt as though I needed more.

What are your favourite dystopian novels? Which would you recommend over all else?

A Gen-X story, The Slap is set in Melbourne with a Greek family at the pivot point. Hector, the protagonist, is married to Aisha, an Indian girl. The two of them are the envy of their friends, set in their perfect lives, with two children. Of course, there is no such thing as perfection, once you peel away the layers, but on the face of it, they are pretty much "perfect." Aisha is vet; Hector is a bureaucrat.

The two of them host a barbecue one afternoon, inviting their friends and family as well as the children. Disagreements between the kids (Spiderman on TV?), unease with the in-laws, and tensions building between some friends sums up the afternoon, although again, on the face of it, everyone seems to be having a good time. But then, the facade falls when Harry, Hector's cousin, slaps a brattish four-year old across the face, and that's the tipping point.

A Gen-X story, The Slap is set in Melbourne with a Greek family at the pivot point. Hector, the protagonist, is married to Aisha, an Indian girl. The two of them are the envy of their friends, set in their perfect lives, with two children. Of course, there is no such thing as perfection, once you peel away the layers, but on the face of it, they are pretty much "perfect." Aisha is vet; Hector is a bureaucrat.

The two of them host a barbecue one afternoon, inviting their friends and family as well as the children. Disagreements between the kids (Spiderman on TV?), unease with the in-laws, and tensions building between some friends sums up the afternoon, although again, on the face of it, everyone seems to be having a good time. But then, the facade falls when Harry, Hector's cousin, slaps a brattish four-year old across the face, and that's the tipping point. Paul Murray's second book, Skippy Dies, has been long listed for the

Paul Murray's second book, Skippy Dies, has been long listed for the  This is probably one of the most gripping books I've read this year. I almost feel guilty that I didn't take Audrey Niffenegger's advice, scrolled across the book cover:

This is probably one of the most gripping books I've read this year. I almost feel guilty that I didn't take Audrey Niffenegger's advice, scrolled across the book cover:

Melancholic - that's the first word that came to my mind when I finished this book. I'm guessing that's how Helen, the protagonist, felt for a major part of her adult life. Her husband, Cal, had been on the Ocean Ranger that sunk in 1982, off the coast of Newfoundland - there were no survivors.

Fast-forward to 2008, which is when this book starts: Helen, now a middle-aged woman, is battling loneliness and misery, as she tries to find some kind of solace in looking after the grandchildren and sewing beautiful wedding and prom dresses as a career. She's tried her hand at online dating, after being persuaded by the children; she's tried yoga; working in a corporation and all in all, it just sounds like she's tried a myriad of things to get over the grief - but to no avail. Does one ever actually get over losing a loved one?

Melancholic - that's the first word that came to my mind when I finished this book. I'm guessing that's how Helen, the protagonist, felt for a major part of her adult life. Her husband, Cal, had been on the Ocean Ranger that sunk in 1982, off the coast of Newfoundland - there were no survivors.

Fast-forward to 2008, which is when this book starts: Helen, now a middle-aged woman, is battling loneliness and misery, as she tries to find some kind of solace in looking after the grandchildren and sewing beautiful wedding and prom dresses as a career. She's tried her hand at online dating, after being persuaded by the children; she's tried yoga; working in a corporation and all in all, it just sounds like she's tried a myriad of things to get over the grief - but to no avail. Does one ever actually get over losing a loved one? I apologise for my thoughts on this book at the very outset. I'm going through a bit of a stressful phase right now, and while normally, it doesn't affect the way I approach books, I'm not completely convinced that it hasn't this time 'round. I mean, The Long Song was longlisted for the Orange Prize, and it's on the Booker longlist as well. It's got to be a good book, right?

Well, I didn't finish it, and it wasn't for lack of trying! I put it aside at 150 pages - my edition had 308 pages, so I did read about half of the book, and it failed to engage me at any level. Strange, because the subject matter is intense and well, more often than not, I end up empathising and sympathising with the protagonists and narrators of such stories. This time - absolutely nothing.

I apologise for my thoughts on this book at the very outset. I'm going through a bit of a stressful phase right now, and while normally, it doesn't affect the way I approach books, I'm not completely convinced that it hasn't this time 'round. I mean, The Long Song was longlisted for the Orange Prize, and it's on the Booker longlist as well. It's got to be a good book, right?

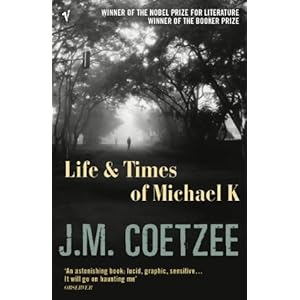

Well, I didn't finish it, and it wasn't for lack of trying! I put it aside at 150 pages - my edition had 308 pages, so I did read about half of the book, and it failed to engage me at any level. Strange, because the subject matter is intense and well, more often than not, I end up empathising and sympathising with the protagonists and narrators of such stories. This time - absolutely nothing. Life and Times of Michael K won the Booker Prize in 1983, and it's been one of Coetzee's books that I've wanted to read for a really long time. The name intrigued me: who is Michael K? And, what is it about his life and times that merits a novel?

Life and Times of Michael K won the Booker Prize in 1983, and it's been one of Coetzee's books that I've wanted to read for a really long time. The name intrigued me: who is Michael K? And, what is it about his life and times that merits a novel?

Ludo, born in the favela of Heliopolis (a shantytown), is "lucky." He's escaped a life of squalor, on being formally adopted by the extremely rich Carnicelli family, who have also hired his mother as a cook in their farmhouse.

Ludo, born in the favela of Heliopolis (a shantytown), is "lucky." He's escaped a life of squalor, on being formally adopted by the extremely rich Carnicelli family, who have also hired his mother as a cook in their farmhouse.

There's a thin line between reality and fiction; they oft' reflect each other very closely, so much so that the line is indiscernible. But - what happens when reality starts imitating fiction?

That's the basic premise of Spark's 1981 novel, starring Fleur Talbot: an aspiring writer in London in the 1950s. She's writing her first novel, Warrender Chase, but she needs a job to get by while she finishes it. And so, she takes up the position of the secretary to Sir Quentin Oliver, and his brainchild: The Autobiographical Association.

There's a thin line between reality and fiction; they oft' reflect each other very closely, so much so that the line is indiscernible. But - what happens when reality starts imitating fiction?

That's the basic premise of Spark's 1981 novel, starring Fleur Talbot: an aspiring writer in London in the 1950s. She's writing her first novel, Warrender Chase, but she needs a job to get by while she finishes it. And so, she takes up the position of the secretary to Sir Quentin Oliver, and his brainchild: The Autobiographical Association. In terms of books being confusing and complex, this one ranks right up there. New characters being introduced every couple of pages, the story taking dramatic turns, changing from showing corruption while trading in the 18th-19th century to a surreal adventure story, and there's a love story thrown in, just for good measure as well.

But no - that's not all. In fact, that's simplifying it much.

In terms of books being confusing and complex, this one ranks right up there. New characters being introduced every couple of pages, the story taking dramatic turns, changing from showing corruption while trading in the 18th-19th century to a surreal adventure story, and there's a love story thrown in, just for good measure as well.

But no - that's not all. In fact, that's simplifying it much. Sarah Waters' The Night Watch is the third novel I've read by her, and it's as different as the previous two as it can be. While one was a gothic ghost story set in Warwickshire (

Sarah Waters' The Night Watch is the third novel I've read by her, and it's as different as the previous two as it can be. While one was a gothic ghost story set in Warwickshire ( In January 2009, I was introduced to the wonderful world of David Mitchell by a friend, who lent me the surreal

In January 2009, I was introduced to the wonderful world of David Mitchell by a friend, who lent me the surreal