"The horror! The horror!" is one of those phrases that will haunt one, long after the last page of the book is turned. This book, or novella, is a ninety page almost-monologue, where the narrator is Marlow, who recounts his adventures searching for Mr. Kurtz in the darkness of Africa. Honestly, despite some incredible lines, I couldn't wait for the book to end. Yes, I know it's a classic, describing the horrors of the ivory trade in the Congo, and is one of those must-reads. However, the emphasis on the allegory of darkness being the heart of the African jungle, or the darkness that pervades the hearts of the European imperialists upon entering here, resulted in me struggling through. For the most part, I like layered narratives, overflowing with metaphors (or any literary device, really), but, to me, this almost came across as forced. Mr. Kurtz, who Marlow only meets in the last third of the book, dominates the narrative. By all accounts, prior to his arrival in the Congo, Mr. Kurtz was a remarkable man. However, as heard through the grapevine, his adventures in the jungles show him as anything but. Thieving, looting, killing, and other barbaric acts seem to define his time in the Congo, while the primary mission that the Company had sent him on was to civilise this uncivilised world, while sending back ivory. Was his fall from grace a result of his environment, or was it simply his innate self being revealed at an opportune moment?

“But his soul was mad. Being alone in the wilderness, it had looked within itself and, by heavens I tell you, it had gone mad.”

Yet, as Mr. Kurtz lay dying, he acknowledged the futility of his endeavours.

Anything approaching the change that came over his features I have never seen before, and hope never to see again. Oh, I wasn't touched. I was fascinated. It was as though a veil had been rent. I saw on that ivory face the expression of sombre pride, of ruthless power, of craven terror--of an intense and hopeless despair. Did he live his life again in every detail of desire, temptation, and surrender during that supreme moment of complete knowledge? He cried in a whisper at some image, at some vision--he cried out twice, a cry that was no more than a breath: The horror! The horror!

Marlow's observations on his milieu were fascinating, and disheartening. It was incredibly bleak, and while one can take solace in the fact that the observations were based on Conrad's own stay in the Congo which was over a century ago (1890), it still leaves one feeling fairly unsettled.

A slight clinking behind me made me turn my head. Six black men advanced in a file, toiling up the path. They walked erect and slow, balancing small baskets full of earth on their heads, and the clink kept time with their footsteps. Black rags were wound round their loins, and the short ends behind waggled to and fro like tails. I could see every rib, the joints of their limbs were like knots in a rope; each had an iron collar on his neck, and all were connected together with a chain whose bights swung between them, rhythmically clinking.

This is probably going to be my shortest review yet, for I don't really have much else to say. I can see why it's a classic, but... I really didn't enjoy it!

When Wolf Hall won the Booker Prize in 2009, I was slightly disappointed. It was one of those books on both, the longlist and the shortlist, that I didn't want to read. I can't quite put my finger on what it was, but there was zero motivation to read the book.

A couple of weeks back though, I pulled it out from my Chunksters shelf, and decided to give it a go, prepared to abandon it midway. But, from the minute I started it till the time I turned the last page, I was totally mesmerised, and was kicking myself (not literally) for not pulling it down sooner.

When Wolf Hall won the Booker Prize in 2009, I was slightly disappointed. It was one of those books on both, the longlist and the shortlist, that I didn't want to read. I can't quite put my finger on what it was, but there was zero motivation to read the book.

A couple of weeks back though, I pulled it out from my Chunksters shelf, and decided to give it a go, prepared to abandon it midway. But, from the minute I started it till the time I turned the last page, I was totally mesmerised, and was kicking myself (not literally) for not pulling it down sooner. The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay is well - amazing. Not only does this book celebrate the "great, mad, new American art form" and pays a tribute to the spirit of Americana in the 1930s, it simultaneously depicts the despair in Europe during the second World War, and how incredibly disconcerting the war was - both, for the people who had to live it, as well as the people who managed to escape it.

Eighteen year old Josef Kavalier flees Prague in the golem's coffin, leaving his family behind, and ends up in Brooklyn, New York, where he's forced to bunk with his seventeen year old cousin, Samuel Klayman (Clay). The cousins, both aspiring artists, hit it off immediately, and Clay introduces Kavalier to the wonderful world of comic books - in an age where Superman has just hit the stands, where the comic book obsession is rampant, and where there's big bucks to be made, the cousins decide to create their very own super-hero to rake in the money.

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay is well - amazing. Not only does this book celebrate the "great, mad, new American art form" and pays a tribute to the spirit of Americana in the 1930s, it simultaneously depicts the despair in Europe during the second World War, and how incredibly disconcerting the war was - both, for the people who had to live it, as well as the people who managed to escape it.

Eighteen year old Josef Kavalier flees Prague in the golem's coffin, leaving his family behind, and ends up in Brooklyn, New York, where he's forced to bunk with his seventeen year old cousin, Samuel Klayman (Clay). The cousins, both aspiring artists, hit it off immediately, and Clay introduces Kavalier to the wonderful world of comic books - in an age where Superman has just hit the stands, where the comic book obsession is rampant, and where there's big bucks to be made, the cousins decide to create their very own super-hero to rake in the money. Yay! I've finished all of Sarah Waters' novels. That's the first thought that crossed my mind after I finished this book, and it was immediately followed by a pang of disappointment, for now I have to wait for her next book to be released, before I can lose myself in one of the wonderful worlds she masterfully creates.

Tipping The Velvet is Sarah Waters' debut novel, and it's quite impressive. Set in Victorian England, this is a coming-of-age story written in first person, where the narrator is Nancy Astley, or simply, Nan.

Yay! I've finished all of Sarah Waters' novels. That's the first thought that crossed my mind after I finished this book, and it was immediately followed by a pang of disappointment, for now I have to wait for her next book to be released, before I can lose myself in one of the wonderful worlds she masterfully creates.

Tipping The Velvet is Sarah Waters' debut novel, and it's quite impressive. Set in Victorian England, this is a coming-of-age story written in first person, where the narrator is Nancy Astley, or simply, Nan. I apologise for my thoughts on this book at the very outset. I'm going through a bit of a stressful phase right now, and while normally, it doesn't affect the way I approach books, I'm not completely convinced that it hasn't this time 'round. I mean, The Long Song was longlisted for the Orange Prize, and it's on the Booker longlist as well. It's got to be a good book, right?

Well, I didn't finish it, and it wasn't for lack of trying! I put it aside at 150 pages - my edition had 308 pages, so I did read about half of the book, and it failed to engage me at any level. Strange, because the subject matter is intense and well, more often than not, I end up empathising and sympathising with the protagonists and narrators of such stories. This time - absolutely nothing.

I apologise for my thoughts on this book at the very outset. I'm going through a bit of a stressful phase right now, and while normally, it doesn't affect the way I approach books, I'm not completely convinced that it hasn't this time 'round. I mean, The Long Song was longlisted for the Orange Prize, and it's on the Booker longlist as well. It's got to be a good book, right?

Well, I didn't finish it, and it wasn't for lack of trying! I put it aside at 150 pages - my edition had 308 pages, so I did read about half of the book, and it failed to engage me at any level. Strange, because the subject matter is intense and well, more often than not, I end up empathising and sympathising with the protagonists and narrators of such stories. This time - absolutely nothing. Life and Times of Michael K won the Booker Prize in 1983, and it's been one of Coetzee's books that I've wanted to read for a really long time. The name intrigued me: who is Michael K? And, what is it about his life and times that merits a novel?

Life and Times of Michael K won the Booker Prize in 1983, and it's been one of Coetzee's books that I've wanted to read for a really long time. The name intrigued me: who is Michael K? And, what is it about his life and times that merits a novel?

In a world where twenty-seven year old women are called "spinsters" and they aren't allowed to study further, despite being inclined towards academia, where they still need their mother's permission to carry out certain activities, and where they're bound by society's rules and regulations, this story is about a woman desperately trying to find her place and her footing while her siblings are getting married, having babies and moving ahead.

It's also a story about another woman, a spiritualist, who has been imprisoned due to her involvement in an affair which led to the unfortunate demise of one of her clients. She blames it on the spirits who she interacts with, but there isn't any evidence in her favour.

In a world where twenty-seven year old women are called "spinsters" and they aren't allowed to study further, despite being inclined towards academia, where they still need their mother's permission to carry out certain activities, and where they're bound by society's rules and regulations, this story is about a woman desperately trying to find her place and her footing while her siblings are getting married, having babies and moving ahead.

It's also a story about another woman, a spiritualist, who has been imprisoned due to her involvement in an affair which led to the unfortunate demise of one of her clients. She blames it on the spirits who she interacts with, but there isn't any evidence in her favour. In terms of books being confusing and complex, this one ranks right up there. New characters being introduced every couple of pages, the story taking dramatic turns, changing from showing corruption while trading in the 18th-19th century to a surreal adventure story, and there's a love story thrown in, just for good measure as well.

But no - that's not all. In fact, that's simplifying it much.

In terms of books being confusing and complex, this one ranks right up there. New characters being introduced every couple of pages, the story taking dramatic turns, changing from showing corruption while trading in the 18th-19th century to a surreal adventure story, and there's a love story thrown in, just for good measure as well.

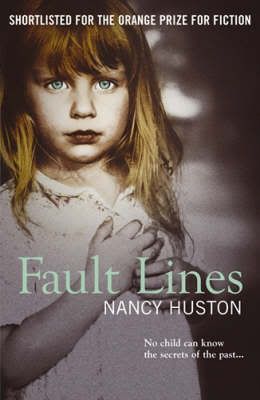

But no - that's not all. In fact, that's simplifying it much. It's the third book I've read this year, where the narrative goes chronologically backwards - the difference being, this time, it follows four generations of six year olds, starting in 2004 and ending in 1944-45.

Sol, a six year old in 2004, believes the world revolves around him, and that he's a genius. Brought up in a pro-Bush environment (Jesus wept), he seems to have a perverse side, as he browses the internet for pictures from the war in Iraq - dead soldiers, raped women, and, there's a reference to the Nick Berg execution as well. This section of the book, to me, highlighted how children today are becoming less innocent and more worldly than back when I was six! Google seems to be playing a massive role in that! To be honest, he almost reminded me of Stewie from Family Guy.

It's the third book I've read this year, where the narrative goes chronologically backwards - the difference being, this time, it follows four generations of six year olds, starting in 2004 and ending in 1944-45.

Sol, a six year old in 2004, believes the world revolves around him, and that he's a genius. Brought up in a pro-Bush environment (Jesus wept), he seems to have a perverse side, as he browses the internet for pictures from the war in Iraq - dead soldiers, raped women, and, there's a reference to the Nick Berg execution as well. This section of the book, to me, highlighted how children today are becoming less innocent and more worldly than back when I was six! Google seems to be playing a massive role in that! To be honest, he almost reminded me of Stewie from Family Guy. Sarah Waters' The Night Watch is the third novel I've read by her, and it's as different as the previous two as it can be. While one was a gothic ghost story set in Warwickshire (

Sarah Waters' The Night Watch is the third novel I've read by her, and it's as different as the previous two as it can be. While one was a gothic ghost story set in Warwickshire (