War destroys all that is left of innocence. It pulls people together, and it drives them apart. People are left asking questions, as they pine for their loved ones, as they try and contemplate the horrors of war, and as they struggle to survive - just so that they can see a better day.

War destroys all that is left of innocence. It pulls people together, and it drives them apart. People are left asking questions, as they pine for their loved ones, as they try and contemplate the horrors of war, and as they struggle to survive - just so that they can see a better day.

And it is this aspect of war that Adichie focuses on in her much-acclaimed novel, Half of a Yellow Sun. The story, based in the 1960s, revolves around the Nigeria-Biafra war - a historical event that has escaped the chapters of most history texts outside Africa - and the massacre, starvation, illness, and fear it brought in its wake, as the Igbo people battled for their independence, which was short-lived. Biafra (even my spell-check doesn't recognize it!), in 1970, returned to Nigeria, and as the book stated: a million people died, in the process.

The story's main protagonists are the twins: Olanna and Kainene, who are poles apart, both in looks and in attitude; their lovers: the 'revolutioary professor' Odenigbo, and the awkward introverted Richard - an expatriate writer, enchanted by Igbo history. And then of course, there's Ugwu, a poor village boy who has come to serve the professor, as a house-boy.

The twins, at the outset, are estranged and distant, for no reason whatsoever. Olanna is about to move in with Odenigbo, and teach in Nsukka, whereas Kainene is looking to take her father's business to greater heights. However, as things turn out, due to love and betrayal, the twins' rift grows deeper, and Olanna finds herself avoiding Kainene. She does, however, adopt Odenigbo's love-child from a brief one-night affair, and finds herself devoted to Baby's health and happiness.

When war breaks out, and strains some of the relationships, while simultaneously bridging the gap in some, we see the weakness and strength in the characters as never before.

Richard, an Englishman (and Kainene's lover) remains in the warzone, and writes articles for the international media, propagating the cause of the Igbo, instead of returning to his motherland. He is disgusted when some white journalists show up, and ask about the unfortunate death of another Englishman. His sarcastic comment at that point is along the lines of: one white person is equivalent to a thousand Biafrans.

Odenigbo finds comfort in his papers, and his theories, but when war breaks out he resorts to alcohol. Olanna, and Ugwu set up a small formal school, as all the schools around them are closed down, and transformed into refugee camps. Kainene, on the other hand, sets up a refugee camp, and tries to ensure that there are enough protein pills and food for everyone - specially the children.

As the characters are introduced, and their role in the story starts shaping up, I couldn't help but marvel at how Adichie's writing shifts from prosaic to poetic. And that, at times, is disconcerting. For example, in the opening chapter, Ugwu is overwhelmed by the richness of his new environment:

He looked up at the ceiling, so high up, so piercingly white. He closed his eyes and tried to reimagine this spacious room with the alien furniture, but he couldn't. He opened his eyes, overcome by a new wonder, and looked around to make sure it was all real. To think that he would sit on these sofas, polish this slippery-smooth floor, wash these gauzy curtains.

and I think that's a beautiful piece of writing - so vivid, and I can close my eyes, and actually imagine Ugwu's wonder, just by the above line.

But then, later on in the book, after the war had started, the descriptions were enough to make me, as a second-hand observer, feel queasy. The below is a snippet when Olanna was on a train, heading back home to her revolutionary lover, after the war had broken out, and the Igbo people were being found out and massacred.

Olanna looked at the bowl. She saw the little girl's head with the ashy-grey skin and the plaited hair and rolled back eyes and open mouth. She stared at it for a while before she looked away. Somebody screamed.

The woman closed the calabash. 'Do you know,' she said, 'it took me so long to plait this hair. She had such thick hair'.

And then there's the scene Richard witnessed at the airport, on landing from England, where his cousin was getting married.

Richard saw fear etched so deeply on to his face that it collapsed his cheeks and transfigured him into a mask that looked nothing like him. He would not say 'Allahu Akbar' because his accent would give him away. Richard willed him to say the words, anyway, to try; he willed him something, anything, to happen in the stifling silence and as if in answer to his thoughts, the rifle went off and (his) chest blew open, a splattering red mass [...]

My favorite character of the book has to be Kainene, just because she's offbeat, and has no illusions (read delusions) of grandeus about herself. While Olanna was occasionally self-piteous, Odenigbo was a character I couldn't relate to. He was an intellect, but came across as a know-it-all. Ugwu was a character I had grown quite fond of, as I could actually relate to some of his thoughts (hats off to Adichie for creating one of the most 'real' characters I've come across, in a long time), but without giving much away, I will say that there are certain things that make a character somewhat irredeemable. And Richard, well, I admired him for sticking to the Igbo people, as though they were his own, but, his character was probably the blandest of them all, if you know what I mean?

In this story about love, loyalty, betrayal, redemption, and survival, Adichie brings up the painful reality of war; unflinchingly discussing gang-rapes, starvation, children dying, and the horrors of air-strikes, where everyone tries to hide in a bunker. In an ironic statement, we see how everything is held together, precariously, as a girl's belly starts to swell, and her mother wonders is she pregnant or is she dying. (a swollen belly indicates 'kwashiorkar', or protein deficiency).

This is a very well-written profound book, and it really wouldn't surprise me if it became a classic of our times. However, in critique, the couple of things I will say are:

In my opinion, the flow of the book was disrupted by how the first section was based in the early 1960s, the second in the late 60s, the third in the early 60s again, and the final section was based in the late 1970s. I didn't quite understand why that was done, because I'm not at all convinced it enhanced the story in any way.

Second, why on earth was a six year old referred to as Baby throughout the whole book? Fair enough, it worked for Jennifer Grey in Dirty Dancing, but, in a warzone, even if you're trying to depict the innocence of a child, the name 'Baby' really doesn't do it. Well, it didn't for me!

And also, I found the last paragraph a weak ending to an otherwise great story. I really do not want to give much away at the time, but, it was an ending that left a bit to be desired. In fact, the way it came about was almost rushed.

Overall, a 7.5 on 10.

Too Much Happiness is a collection of short stories by internationally-acclaimed writer, Alice Munro. Not being a big fan of short stories, I always start a collection tentatively, not really expecting to enjoy it, but hoping to be pleasantly surprised. Munro's

Too Much Happiness is a collection of short stories by internationally-acclaimed writer, Alice Munro. Not being a big fan of short stories, I always start a collection tentatively, not really expecting to enjoy it, but hoping to be pleasantly surprised. Munro's  New York, 1974. The magnificent twin towers are unveiled to the world, and the consensus is that they are ugly compared to the splendid sky-scrapers that grace the New York skyline (the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, Rockefeller Centre etc). But, a marvelous feat from an athlete, Philippe Petit, almost changes the perception. Petit walked across a tightrope between the towers - he danced, he entertained, he wowed, and he enjoyed himself thoroughly, as the New Yorkers below looked up in awe, wondering if the man dancing with the clouds was suicidal, crazy, or if he had some perfectly legitimate reason to be doing what he was. After all, it’s not often, you see someone dancing with the clouds.

New York, 1974. The magnificent twin towers are unveiled to the world, and the consensus is that they are ugly compared to the splendid sky-scrapers that grace the New York skyline (the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, Rockefeller Centre etc). But, a marvelous feat from an athlete, Philippe Petit, almost changes the perception. Petit walked across a tightrope between the towers - he danced, he entertained, he wowed, and he enjoyed himself thoroughly, as the New Yorkers below looked up in awe, wondering if the man dancing with the clouds was suicidal, crazy, or if he had some perfectly legitimate reason to be doing what he was. After all, it’s not often, you see someone dancing with the clouds.  Yay! I've finished all of Sarah Waters' novels. That's the first thought that crossed my mind after I finished this book, and it was immediately followed by a pang of disappointment, for now I have to wait for her next book to be released, before I can lose myself in one of the wonderful worlds she masterfully creates.

Tipping The Velvet is Sarah Waters' debut novel, and it's quite impressive. Set in Victorian England, this is a coming-of-age story written in first person, where the narrator is Nancy Astley, or simply, Nan.

Yay! I've finished all of Sarah Waters' novels. That's the first thought that crossed my mind after I finished this book, and it was immediately followed by a pang of disappointment, for now I have to wait for her next book to be released, before I can lose myself in one of the wonderful worlds she masterfully creates.

Tipping The Velvet is Sarah Waters' debut novel, and it's quite impressive. Set in Victorian England, this is a coming-of-age story written in first person, where the narrator is Nancy Astley, or simply, Nan. About five years back, with the launch of the iPod Shuffle, Apple declared "random is the new order" to the world, as "life is random" so we should "give chance a chance."

What does any of this have to do with Black Swan Green? Well, nothing, really! However, it does have a lot to do with the way I've approached the works of David Mitchell - Unlike some book bloggers (e.g.

About five years back, with the launch of the iPod Shuffle, Apple declared "random is the new order" to the world, as "life is random" so we should "give chance a chance."

What does any of this have to do with Black Swan Green? Well, nothing, really! However, it does have a lot to do with the way I've approached the works of David Mitchell - Unlike some book bloggers (e.g.  A Gate At The Stairs is one of "those" books - beautiful writing, intelligent conversation flowing through the book, a sensitive plot, and a book with great potential.

Tassie is a college student in the Mid-western town of Troy, who finds a job as a baby sitter for Sarah, an affluent restaurant-owner who adopts Emmie, a "biracial" child. Sarah is perpetually busy running the upmarket restaurant, and Tassie ends up spending a fair bit of time mothering Emmie.

A Gate At The Stairs is one of "those" books - beautiful writing, intelligent conversation flowing through the book, a sensitive plot, and a book with great potential.

Tassie is a college student in the Mid-western town of Troy, who finds a job as a baby sitter for Sarah, an affluent restaurant-owner who adopts Emmie, a "biracial" child. Sarah is perpetually busy running the upmarket restaurant, and Tassie ends up spending a fair bit of time mothering Emmie. I finished this book over two weeks ago, and have been struggling to write the review ever since. I honestly hoped I wouldn't have to drag it into the new year, but there you have it...

This is the first Toni Morrison I've read, and I started the book with great trepidation. I've heard phenomenal things about Toni Morrison, and I was intimidated... unsure of what to expect. I really hoped I'd enjoy the book, and it would make me go out and buy more books by Morrison instantaneously, but unfortunately, I was left feeling fairly indifferent. I didn't like the book. I didn't dislike the book... and I'm not accustomed to having that kind of a reaction to a book - especially as I've mulled over it for about two weeks!

I finished this book over two weeks ago, and have been struggling to write the review ever since. I honestly hoped I wouldn't have to drag it into the new year, but there you have it...

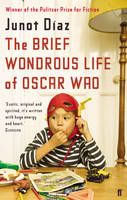

This is the first Toni Morrison I've read, and I started the book with great trepidation. I've heard phenomenal things about Toni Morrison, and I was intimidated... unsure of what to expect. I really hoped I'd enjoy the book, and it would make me go out and buy more books by Morrison instantaneously, but unfortunately, I was left feeling fairly indifferent. I didn't like the book. I didn't dislike the book... and I'm not accustomed to having that kind of a reaction to a book - especially as I've mulled over it for about two weeks! The Brief Wondrous Life Of Oscar Wao won the Pultizer Prize for Fiction in 2008. The protagonist, Oscar, is an overweight American boy (with Dominican roots), who aspires to be the next Tolkien. His interests include writing passionately, role-playing games, comic books, sci-fi and fantasy, and of course, women. However, one bad experience with his first love meant his adolescent nerdliness vaporising any iota of a chance he had for young love. He lives in New Jersey with his demanding difficult-to-please mother, Belicia, and his rebellious punk sister, Lola.

While the protagonist of this book is Oscar, it's narrated by Yunior - Oscar's roommate from college, as well as a love interest of Lola. Also, this is not a book about "the brief wondrous life of Oscar Wao" - instead, it's an epic story of the curse (fukú) that Oscar's family has been subject to, for the past two generations, in the hands of Trujillo, a dictator in the Dominican Republic in the mid-1900s.

The Brief Wondrous Life Of Oscar Wao won the Pultizer Prize for Fiction in 2008. The protagonist, Oscar, is an overweight American boy (with Dominican roots), who aspires to be the next Tolkien. His interests include writing passionately, role-playing games, comic books, sci-fi and fantasy, and of course, women. However, one bad experience with his first love meant his adolescent nerdliness vaporising any iota of a chance he had for young love. He lives in New Jersey with his demanding difficult-to-please mother, Belicia, and his rebellious punk sister, Lola.

While the protagonist of this book is Oscar, it's narrated by Yunior - Oscar's roommate from college, as well as a love interest of Lola. Also, this is not a book about "the brief wondrous life of Oscar Wao" - instead, it's an epic story of the curse (fukú) that Oscar's family has been subject to, for the past two generations, in the hands of Trujillo, a dictator in the Dominican Republic in the mid-1900s. I'm trying to read all the Booker winners, in the next couple of years. This painstakingly dull book, filled with unengaging characters and a pointless plot adds a serious blemish to my plan at the very outset. I struggled through the first thirty pages, and struggled some more 'til I hit page 89, in a week... And then... then I just gave up, and figured this book is not for me. I mean, what a gigantic waste of my reading time!

I'm trying to read all the Booker winners, in the next couple of years. This painstakingly dull book, filled with unengaging characters and a pointless plot adds a serious blemish to my plan at the very outset. I struggled through the first thirty pages, and struggled some more 'til I hit page 89, in a week... And then... then I just gave up, and figured this book is not for me. I mean, what a gigantic waste of my reading time!  War destroys all that is left of innocence. It pulls people together, and it drives them apart. People are left asking questions, as they pine for their loved ones, as they try and contemplate the horrors of war, and as they struggle to survive - just so that they can see a better day.

War destroys all that is left of innocence. It pulls people together, and it drives them apart. People are left asking questions, as they pine for their loved ones, as they try and contemplate the horrors of war, and as they struggle to survive - just so that they can see a better day.