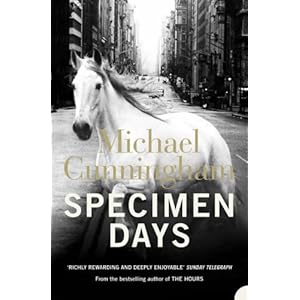

I absolutely adored Cunningham's The Hours, and couldn't wait to read another book by Cunningham. And then - then I saw the cover of this one, and I was in love! I knew I just had to read the book. And so, I did.

Essentially, Specimen Days is a collection of three novellas, as opposed to one novel. Like The Hours, there are three inter-linked stories, and like The Hours, a famous literary persona makes an appearance (in this case, it's Walt Whitman).

I absolutely adored Cunningham's The Hours, and couldn't wait to read another book by Cunningham. And then - then I saw the cover of this one, and I was in love! I knew I just had to read the book. And so, I did.

Essentially, Specimen Days is a collection of three novellas, as opposed to one novel. Like The Hours, there are three inter-linked stories, and like The Hours, a famous literary persona makes an appearance (in this case, it's Walt Whitman).

However, unlike The Hours, this novel is set in entirety in New York, and it's set across time. The first story goes back to the era when Whitman was still alive, during the time of the Industrial Revolution; the second story is almost current-day set in a post 9-11 New York haunted by terrorist threads and the final story is set in a futuristic society of half-humans and aliens.

In an almost Cloud Atlas-esque fashion though, the protagonists across the stories seem to be re-incarnations of themselves. There's Simon and Catherine (Cat, Catareen) as the two adults and Lucas (Luke) as the adolescent. A bowl makes a reappearance across the ages as well, as does the poetry of Walt Whitman.

The first story, In The Machine, is set during the time of the Industrial Revolution (nineteenth century), where Lucas, a young boy, starts working in the factory where a terrible accident led to his brother's unfortunate demise. Lucas, who spouts Whitman (a present-day poet at the time) incessantly, reaches the haunting conclusion that the machines are evil and are trying to pull the living in, as they did to his older brother (Simon). His innocence and adamance is almost heart-breaking as he tries to convince Simon's fiancee, Catharine, to stay away from the "machine."

And then we move to The Children's Crusades, where Cat plays the leading role, as a woman who is a police psychologist. Amidst other things, she mans the phone line where would-be terrorists and assassins call up and drop hints about potential upcoming bombs. The latest set of terrorism seems to be coming from a group of children, who quote Whitman's Leaves of Grass, hug a random stranger, and then the bomb detonates...

Finally, there's Like Beauty, set in a post-apocalyptic New York, swarming with aliens and androids. Simon, an alien, who is programmed to recite Whitman at the unlikeliest of times, runs away with Catareen, a lizard-like alien, in search for the man who created him. They take a trip across the country, along with Luke, and manage to find a place on a spaceship that will take them to paradise - a different planet.

The characters are wonderfully drawn across all three stories, and the rapport between them is extremely real. Some of them are outsiders, whereas some of them are searching for a place where they belong. The way things are described had me nodding along in agreement, specially in the second novella.

"Look around," she said. "Do you see happiness? Do you see joy? Americans have never been this prosperous, people have never been this safe. They've never lived so long, in such good health, ever, in the whole history. To someone a hundred years ago, as recently as that, this world would seem like heaven itself. We can fly. Our teeth don't rot. Our children aren't feverish one moment and dead the next. There's no dung in the milk. There's milk, as much as we want. The curch can't roast us alive over minor differences of opinion. The elders can't stone us to death because we might have commited adultery. Our crops never fail. We can eat raw fish in the middle of the desert, if we want to. And look at us. We're so obese we need bigger cemetery plots. Our ten-year-olds are doing heroin, or they're murdering eight-year-olds, or both. We're getting divorced faster than we're getting married. Everything we eat has to be sealed because if it wasn't, somebody would put poison into it, and if they couldn't get poison, they'd put pins into it. A tenth of us are in jail, and we can't build new ones fast enough. We're bombing other countries simply because they make us nervous, and most of us not only couldn't find these countries in a map, we couldn't tell you which continent they're on. [...] So tell me. Would you say this is working out? Does this seems to you a story that wants to continue?"

The title itself is inspired by one of Walt Whitman's works - something I'm not very familiar with, which makes me feel slightly guilty, for I don't think I missed a lot in the book. Some of the references though seemed unnecessary, but I think that might be a result of me not really seeing the whole picture, as I'm not well-versed with Leaves of Grass, or much of Whitman's work/thoughts.

Have you read Specimen Days? Or any other Cunningham?

If you've read Specimen Days, do you think knowing a lot more about Whitman's work would improve the reading experience manifold?

It's not often a book leaves me completely speechless. Wowed. Awestruck. Absolutely blown away. But then again, it's not often that I come across a book like Michael Cunningham's The Hours. Both,

It's not often a book leaves me completely speechless. Wowed. Awestruck. Absolutely blown away. But then again, it's not often that I come across a book like Michael Cunningham's The Hours. Both,